Intro

I love stumbling across paired stories. Those rare and curious times when two different writers take on the same concept around the same time. There are plenty of Hollywood examples. Armageddon and Deep Impact. White House Down and Olympus Has Fallen. The Illusionist and The Prestige. It feels like two philosophers each making their own argument in the public forum and by reading their story, you see the full journey to their conclusion.

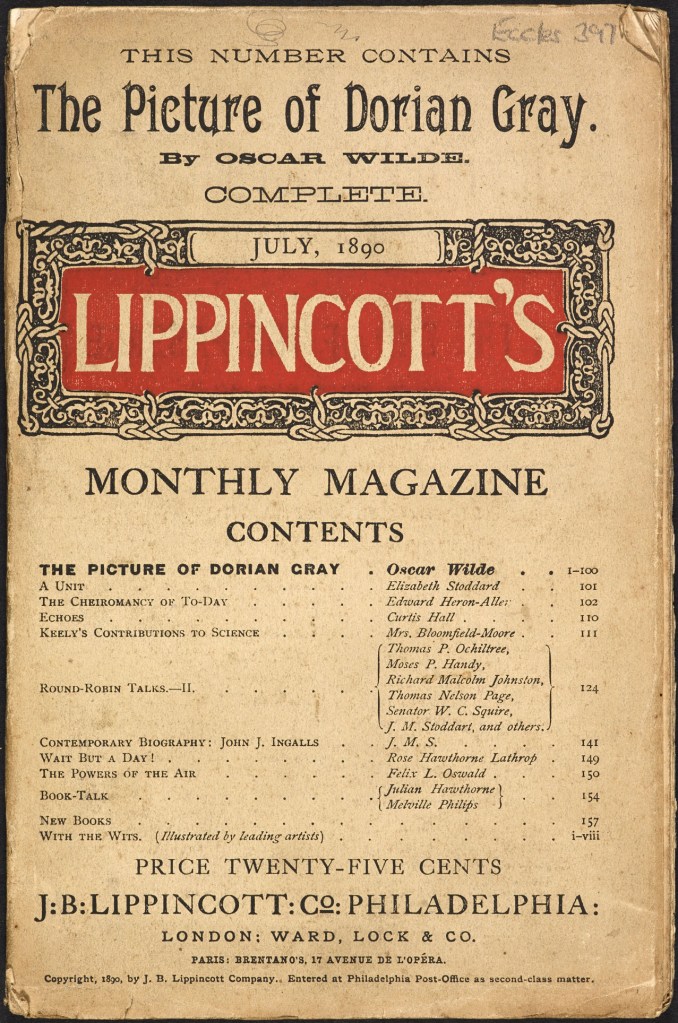

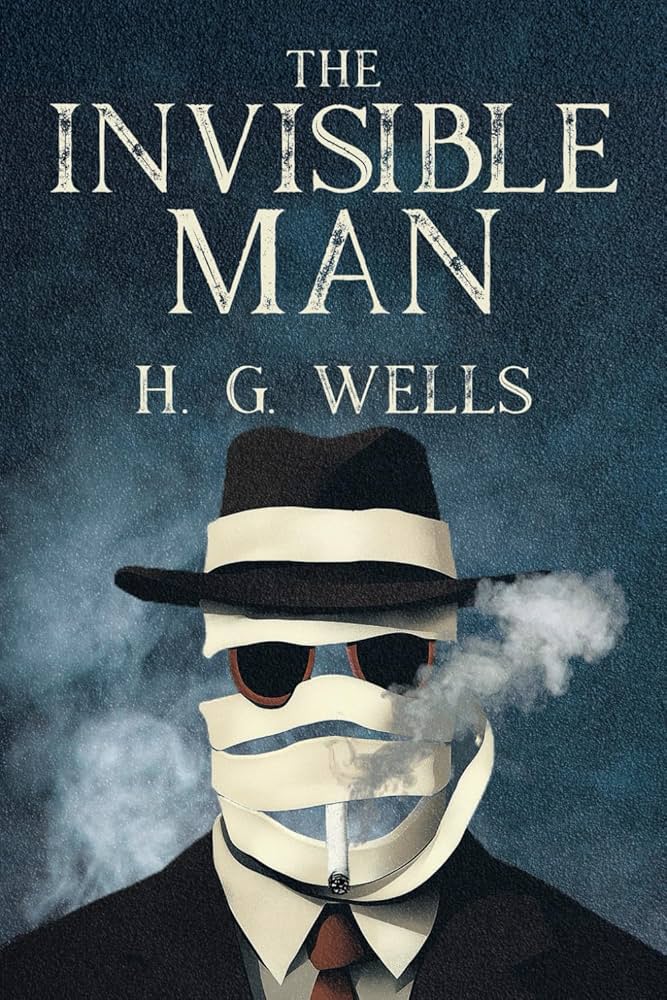

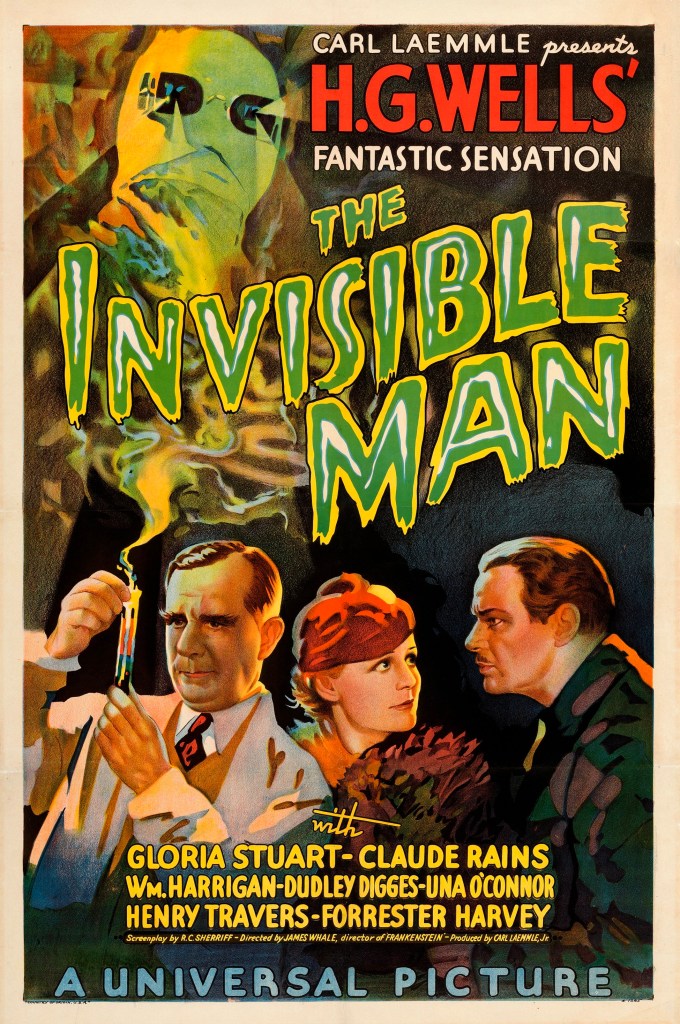

In the 1890s, two of the greatest authors of their time wrote two of their greatest books. First was The Picture of Dorian Gray. Originally published in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine in 1890 and expanded into a novel in 1891, it stands as Oscar Wild’s only novel in a career writing plays and poetry. Then in 1897, two years into HG Wells half-century long science fiction career, he released The Invisible Man.

Both stories have been told and adapted and shared millions of times over the years, both stories have outlived their creator. And while the two stories on their face appear completely different, both try to answer the same question: What would a person become if they could act without consequence?

To me, these two books are my favorite example of paired works. An opportunity to see a sci-fi writer and a playwright approach the same philosophical concept. A chance to observe two masters each bring their own unique perspectives and reach vastly different conclusions.

Two villainous leads

When a skilled storyteller knows what kind of story they want to write, even if they don’t know the details, the nature of the story trims down the possibilities. If you want to tell a story of someone reconnecting with a community, it means they had a community to begin with. If you’re writing a revenge power fantasy, it usually helps for the main character to at one time in the past be a uniquely skilled fighter. I like to call it ‘novel-writing algebra’.

In the case of a theme like ‘no consequences’, both storytellers realized they had to start from the same place. To truly explore the space, each story’s protagonist had to be more villain than hero.

The Picture of Dorian Gray tells the story of eponymous Dorian Gray, a young man that values his appearance and youth above all other things. After realizing all his cruelties appear on his portrait rather than being reflected onto his person, he embraces his worst tendencies. Hurting those who love him, extorting, murdering, everything he can think of in one long hedonism treadmill.

The Invisible Man’s protagonist is just as reprehensible, but in his own way. Jack Griffin, for what it’s worth, earns his invisibility. He discovers the means to turn living tissue invisible and uses it to burgle, rob, and threaten. But it wasn’t the invisibility that made him that way. He robbed his father even while his skin was still opaque. Throughout the book he is teasing and cruel to the people he is closest to. The kind of man no person would want to associate with in real life.

A pair of cruel characters for a pair of moral lessons. How else could you teach it? If you start with a good character using their protection for a good cause, you end up with The Invisible Woman saving the world in a comic book.

Both authors realized that in order to explore the concept of consequence fully, they needed a bad actor to exploit the situation.

Freedom from Consequence

At the question of ‘What does a bad person do without consequences?’, our two authors diverge.

HG Wells goes down the obvious path. Mayhem, havoc, and immediate self-serving cruelty. In every action, The Invisible Man acts as untouchable as he feels. HIs dealings with others are impatient and demanding. As the story goes on, his ambition grows. His vision expands from short-term robberies to an ‘epoch of the invisible man’ by means of violent threat.

A bully. That’s all Griffin is. The second he gets an ounce of power, he stretches it to its utmost with no plans for the future. At the outset, this feels like the only answer. A person without fear of reprisal tries to force the world into their vision of things.

But Oscar Wilde’s take is vastly different.

Dorian Gray isn’t an ambitious man, he’s petty. Looks matter more than character. Charm more than soul. Over the course of a lifetime, consequences seem to evade him. When a man comes to avenge his sister, he realizes that Dorian Gray couldn’t possibly be the man from 20 years ago, after all he hasn’t aged a day.

When Dorian is given the freedom to do as he’d like, he doesn’t shape the world, he plays with it. People and institutions become toys to be tinkered with, broken, and tossed away. Even when hiding a body he handles the whole situation with a cold psychopathy. The dead man isn’t a person, it’s a thing. Dorian accumulates wealth and connections all through the world and his capacity to do expands, but the answer to ‘what will he do’ seems to come down to a single answer: whatever he feels like.

Although Griffin is supposed to be the more intelligent of the two characters, Dorian without a doubt makes better use of his power. He feels more real too, like one of thousands of kids born and raised into wealth under a system built to protect and empower them. A lifetime with no fear gives him a detachment from his actions. Everything is a game to be played and moved on from.

When the hammer comes down

Both authors reach similar conclusions at the end of their stories. Even if a person sees no immediate consequences to their actions, there are always consequences.

The Invisible Man gives the easy answer. If a person behaves cruelly for a long time the world will eventually hunt that person down and deliver the consequences nature tried to protect them from. Jack Griffin’s final moments are spent being beaten by a mob. Victim not of a single action, but the sum of all his behaviors.

I don’t know how much I believe it. There are plenty of stories of people getting away with their crimes, even in a court of law. Even tyrants die of old age from time to time.

Oscar Wilde gives a different vision of ‘consequence’, and one that is clear from the beginning of the book. With every sin Dorian Gray commits, his portrait changes. A cruel smile at the edge of his lips, bloodstains, scars. The portrait isn’t just a magical painting, it is a reflection of Dorian’s soul, and for me, the better answer to the question of consequence.

Even if the world never retaliates. Every evil action distorts a person’s truest self. A murder doesn’t just stain the hands, it stains the heart. By the end of Dorian Gray’s life, the portrait doesn’t even look human. Terrible deeds have reshaped the man so far as to cut out his humanity entirely.

Conclusion

It’s impossible to move through life without seeing the occasional villain. I think that’s what makes the theme of ‘consequence free action’ resonate. Injustice is a part of life. Maybe what that makes these stories palatable is knowing the author will deliver some kind of justice by the end.

To me, The Invisible Man has the feel of a comforting moral tale for the upstanding in society. Eventually evil will be held accountable, even if it takes awhile.

But The Picture of Dorian Gray gives an answer that feels truer to life. Justice is not exact. Sometimes the worst of the worst escape their consequences and the good suffer in their wake. The only thing that can truly be said of the person that acts with no fear of reprisal is that they will eventually lose their personhood entirely and by the end of their life become unrecognizable to the world around them.