For thirty years, strategy game players have been reckoning with the harsh reality that a computer might be able to play a game better than them. Beginning in 1997 with Kasparov vs Deep Blue and ending with Lee Se-Dol vs AlphaGo, AI inched ahead of human performance year by year, culminating in their total victory.

I love that tension, the open question that floats in the air with every game, ‘Can humanity win?’. Every victory and every defeat carried enormous weight. It’s the heart of my novel, The Human Countermove, strategy games and the fight against a mentally superior enemy.

The challenge with writing a strategy book is creating strategies that feel authentic and clever. The kind of ideas that are convincingly grandmaster in skill, but understandable to the general public. In order to achieve that, I had to learn from the best.

Kasparov vs Deep Blue (1997)

This game is the seed at the center of my book. The tipping point for humanity, the moment we realized computers could out-think people. In 1996, Kasparov won 4-2.

In 1997, they had a rematch, Deep Blue won 3.5-2.5.

Those two matches record the exact year engineering overtook training.

My favorite moment from the 1997 match comes in game 2, when Kasparov accused the Deep Blue team of cheating by having a Grandmaster help with a move. Even a computer can get illegal assistance from time-to-time it seems.

But the conflict of the moment is what really captures me. On the one hand, we want to believe a person is capable of outperforming a computer. On the other, what an incredible feat it is to reproduce the mind of a genius with a bit of code and training. Caught in between, the audience cheers both sides, athletic feat against human ingenuity.

Kasparov has a list of mistakes he says he regrets about that match. Moments he could have snatched a draw from a defeat, a victory from a stalemate. The thing is, if he had won, all it would have done is stall the inevitable. Instead of discussing the 1997 Kasparov vs Deep Blue match, we’d be discussing the 1998 Kasparov vs Deep Blue match.

It’s all of this I try to capture in my book. The tension, the conflict, the regret, and the determination to beat the unbeatable.

Now when Chess Engines and AI models face off against one another, they are a tier beyond our best players. A mentor for grandmasters like Magnus Carlsen, and something beyond the rest of our comprehension.

The Opera Game (1858)

This is a lighter game. The Opera game was played by Paul Morphy and The Duke of Brunswick over a century ago. It’s one I draw inspiration from in my novel not as a strategic tool, but as a piece of chess culture. The Opera Game represents the beginning of a chess student’s education, one of the very first games a novice will be introduced to.

Paul Morphy makes strong, understandable decisions against a much weaker opponent, rapidly gains the advantage, and wins in style. But it’s not just a game, it’s a story. The best in the world dragged into the Duke’s box to play a chess game in the middle of an opera. For beginners, it weaves a romance around chess, and attaches a narrative to one of their first lessons.

In my book, the protagonist Zouk does a lot of teaching on the side, as many professional players find themselves doing. When an opportunity to lecture to a big audience comes around and he realizes the inexperience of his listeners, he abandons the esoteric analysis had prepared, and leans on a tried and true classic with a fun story, The Highway Game.

Go: Lee Se-Dol vs AlphaGo (2017)

Lee Se-Dol vs AlphaGo ended in a 1-4 result. For those of us that had been tracking the development of computers since Deep Blue’s game against Kasparov, seeing AlphaGo take its victory wasn’t a surprise. Go is much more computationally difficult than chess, but Moore’s Law is a powerful force.

But did you notice the scoreboard? Lee Se-Dol won the fourth game. That was an upset.

Against Google’s best engineers and decades of neural networking and algorithmic design, a human being managed to snatch victory, and it all came from a single move. Move 78.

That move has been gone over, analyzed, and studied for years. It’s believed Move 78 pushed the game into a uniquely complicated position, a position AlphaGo couldn’t calculate. A blind spot in the computer’s play that drew out blunder after blunder.

Lee Se-Dol was like a grandmaster Quality Assurance tester, noticing where AlphaGo was weak and pushing it further and further down that path until its behavior was sub-par. Basically, Lee Se-Dol found a bug.

Even when it seemed impossible, a person beat the unbeatable.

The Hippo and Various Anti-AI Strategies

Since Kasparov vs Deep Blue, a thousand Chess engines have burst onto the scene. Anyone willing to run a bit of code on their computer and risk getting banned can play like a grandmaster. To beat such unsavory characters, grandmasters have had to develop a special set of tools. First and foremost is time.

Consider two games. One gives each player an hour to make all their turns, the other gives each player a minute to make their turns. The first game is deeply thought out, with strong moves that remove all chances of counterplay. The second is superficial, moves borne more from training than thought.

In tight time controls, using a chess engine becomes a liability. The grandmaster can play from their subconscious, but the cheater is stuck waiting for the ‘perfect answer’ from the machine.

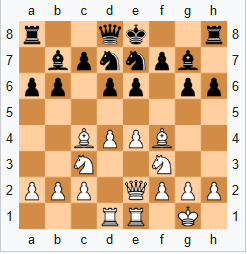

Thus we meet The Hippo. The Hippo slows the game down to a crawl. Pieces only move forward a square or two, then build a near-impenetrable fortress. As the opponent approaches, the grandmaster makes every effort to close down the position, keeping the number of moving pieces to a minimum.

With each move, the cheater loses a little more time, and the walls close tighter around them.

As their time dwindles, the cheater is forced to throw in a few of their own moves. These usually turn out to be of a significantly lower quality than what a chess engine can put out. Once the grandmaster has stripped the cheater of their chess engine, they unravel all the complexity of The Hippo and go in for the kill.

Once again, complexity and time as weapons to beat an overthinking machine.

The Battle of Cannae and Real-Time Strategy Games

I love real-time strategy games. The feeling of making a plan, facing the hard truths of reality, making adjustments, and turning the battle in your favor is exhilarating. And they’re so different from a game like Chess or Go. In Chess and Go, the entire shape of the board is transformed in a single move.

In Real-Time Strategy games like Starcraft, you’re making a new move every second, and it’s only when you add all those little decisions up that you end up with a result.

And in games like that, there’s one particular battle result that everyone is chasing.

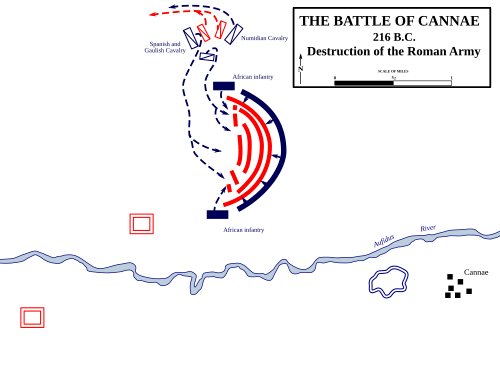

During the Second Punic Wars, Hannibal faced a much larger Roman force and turned the battle completely in his favor. The trick? Draw the enemy in, encircle them completely, then tighten the trap.

The game in my book, LINE, isn’t like Chess or Go. It’s a little more practical in nature. In theory, the game is playable on a field, not that most people would enjoy the feeling of being shot by a rubber bag. Because of the practical realities of squadrons facing off against one another, tactics like Chess’ fork and pin don’t translate.

But what does translate, is the greatest military trap of all time. Let the enemy over-extend themselves, wait for the right moment, and strike.

Final Words

There are plenty of other strategy games I no doubt pulled inspiration from. Things like the Total War games, Role Playing Games, X-COM, but Chess was my guiding star. It’s funny, once you open your mind to a question like, ‘how does a person beat an AI in strategy?’, you realize how many other people already pondered the same question.

AIs have been kicking Mankind’s collective butt for thirty years. It’s nearly impossible to imagine a person turning it around on them. But nearly impossible is still possible, it only takes the right person and the right techniques to turn things around. Even when the robot brains out-think us on every front, we can still squeak out a victory every now and then. Especially when we’re learning from everything that’s available.

In The Human Countermove, my protagonist Zouk Solinsen is the right person with the right techniques. The skills to outsmart computational genius.

My debut novel, THE HUMAN COUNTERMOVE is now available for purchase!