The following is a discussion of Dan Simmons’ Hyperion and Fall of Hyperion books. Spoilers abound.

My Discovery

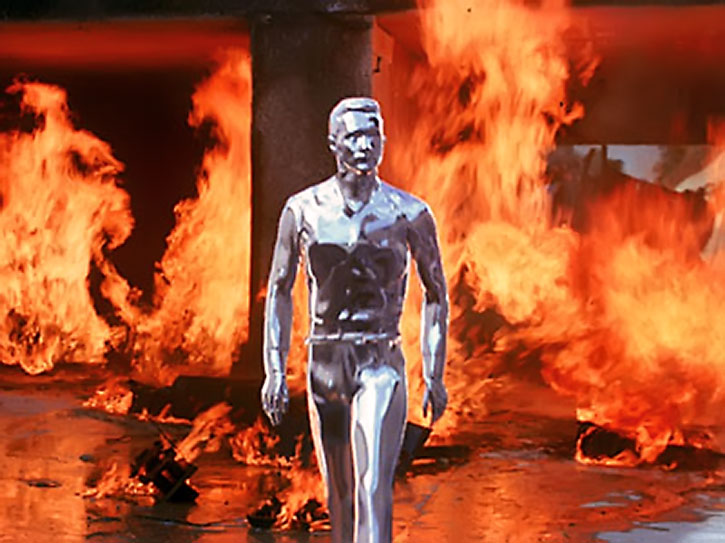

So there I was, reading through Fall of Hyperion, following the story of Fehdman Kassad. He had finally met up with his Moneta right after they had tried to kill each other. Then the text of the book read ‘her shifted like quicksilver’. I don’t have a lot of experience with quicksilver, and even less with the shifting variety. My mind jumped to a single image. The T-1000 from terminator.

Well my brain started making connections. Connections that probably shouldn’t be made, the kind of connections that steal a story’s originality. I always pictured The Shrike as a light-grey metal monster, it wouldn’t be impossible to imagine its skin shifting like quicksilver either. A little later, the book revealed The Shrike had been sent back in time from the future. And the next time The Shrike made an appearance in the story, the next time he slowly walked towards one of the characters with murderous intent. I heard that iconic drumbeat in my head.

Dun dun dun dun dun.

And it all came together.

Recasting Hyperion

The funny thing here is that the T-1000 is from Terminator 2, which came out in 1991, the same year as Fall of Hyperion, no way for Dan Simmons to have copied the movie directly. Maybe it was a case of parallel thinking. Maybe Dan Simmons saw the first Terminator and was inspired. Nevertheless, if we stretch the connections between these two stories, there’s a lot more that matches up than you’d think.

So the Shrike is The Terminator, sent back in time to fulfill the wishes of a devious far-future net of alien consciousness. In Terminator, it was called Skynet. In Hyperion, they call it The Ultimate Intelligence. Does it go further than that? Well, as we discover in the book, The Shrike isn’t just here to be evil, it’s here to find and eliminate one particular target. The future Empathy branch of Humanity’s Ultimate Intelligence. In other words, eliminate John Connor before he could become the leader of the human resistance.

And we can’t ignore the main character of The Terminator Franchise. The series may be named after the T-800 and T-1000, but Sarah Connor is without a doubt the protagonist of the series. Let’s meet her Hyperion counterpart, Brawne Lamia! In my first review of Hyperion, I didn’t talk much about her, but she is effectively the main character in The Fall of Hyperion’s massive ensemble. She’s the one who gets the big flash-forward to an apocalyptic future. Of course, instead of Skynet going to war with humans, we have an AI Ultimate Intelligence at war with a Human Ultimate Intelligence.

She’s also, as we discover at the back of the book, the mother of the future Empathy branch of Humanity’s Ultimate Intelligence. Literally Sarah Connor, the mother of John Connor! We even have a conversation between Brawne Lamia and one of the super AI’s Ummon where it says there are many probable futures, but the one with two Gods fighting each other is the most likely, which is dangerously close to “The future is not set. There is no fate but what we make for ourselves”

Now the most forgotten member of the Terminator story, Kyle Reese. The soldier from the future trying to keep Sarah Connor alive. Who could this be? There’s only one candidate. Moneta, the mysterious woman with ties to The Shrike who is in love with Fehdman Kassad. She is literally sent from the future to watch The Shrike’s actions. Unfortunately for Kassad, she’s a little more concerned with her present then staying in the past, and the poor guy is dragged into an intergalactic war against millions and billions of Shrike. The one thing worse than being hunted by The Terminator is being brought into the future and fighting armies of T-1000s.

All right, I confess, those are all the direct character connections, as far as I could find them. The Fall of Hyperion is an ensemble story, a book that follows about 9 different main characters through the plot. And in order to make that story fulfilling, it takes a few detours along the way.

When Hyperion Rises Above Terminator

In the first few Terminator movies, the plot is about keeping Sarah Connor alive. It’s not about stopping Skynet or reshaping what’s to come. Humanity basically plays defense, keeping things as they are, no matter how dystopian they turn out, because it could always get worse. That’s not good enough for Hyperion.

CEO Meina Gladstone is humanity’s champion. The politician in the right place at the right time to make historic decisions. So much of The Fall of Hyperion is about slowly uncovering what kind of nightmare awaits us in the future, and how it happened. There’s a general sense that some kind of apocalypse is coming. Father Dure, cursed back to life, is taken on a journey through the most upsetting aspects of the future. Cruciforms used on billions to drag them back to life again and again as nothing but human chattel.

New questions arise. How was humanity shackled like this? Was it these strange Ousters from the edge of the galaxy? Where does the Technocore come into play? Why does the Technocore keep helping humanity when it seems like their two paths are in constant opposition?

The most chilling moment of the book is a subtle one. The apocalypse appears to have come, a ragtag group called The Ousters has proven far more capable and widespread than anyone suspected, and humanity is getting desperate. In their desperation, they ask the technocore for a solution. The Deathwand. We don’t need a character going on a long diatribe to understand why a device like that could be dangerous. The technocore explains its many safeties. And in a long, long book, one little warning is enough to telegraph everything. “Those must have been the same promises the Technocore made moments before the Kiev Incident.”

It’s like witnessing the minutes before Skynet was turned on, but worse. It isn’t just a mistake from humanity, but a cleverly designed ruse that, in the pit of your stomach, you know will end humanity as a race forever.

And this is where we go beyond Terminator. The world of Terminator is spanning, but the plot is small: the survival of a single character, the journey of Sarah Connor. Hyperion doesn’t just tell the story of the person who is meant to turn the tide, it tells the story of the moment humanity’s hope was nearly snuffed out.

Is it Really Terminator?

Mark Twain once said, ‘There is no such thing as an original idea’.

Outer Limits is a tv from 1964, one of its episodes, ‘soldier’, tells the story of two future soldiers sent back in time to change the future. The story ‘I have no mouth and I must scream’ depicts a moment when human decision is removed from nuclear war, eventually resulting in an AI called the Allied Master computer wiping out all of humanity but a few it keeps alive underground as chattel.

These ideas existed before Terminator (Although if you ask writer Harlan Ellison, they started with him).

Dan Simmons takes the original concept of Terminator, and elevates it into something so much bigger. He rewrites a battle between two armies to a war between Gods. We initially think it’s just a nice metaphor, but by the end, it’s literal. A Titan and A God in eternal battle at the end of time. Instead of hard drums and rock, he uses poetry and classical epics to give the story a literary significance. The Terminator is iconic. But the Shrike is evil incarnate. Like The Terminator turned up to eleven.

But the best part of these books is when they diverge from The Terminator storyline, when we take time to get to know the ensemble that surrounds the main story. I could barely remember the name Kyle Reese when I wrote this up, but the names Father Dure, Fehdman Kassad, Sol Weintraub, Martin Silenus, and Brawne Lahmia stick with me. Tiny players in the grand story of divine war, but its their stories that stick with you.